Dr Lucy Gossage. Exercise and Cancer: What Do Healthcare Professionals Working in General Practice Need to Know? – Medscape – December 15, 2025. https://reference.medscape.com/cc1/p10/exercise-and-cancer-what-do-healthcare-professionals-working-2025a1000qlf#1

Exercise and Cancer: What do Healthcare Professionals Working in General Practice Need to Know?

Dr Lucy Gossage discusses the benefits of exercise as an underutilised therapeutic intervention for cancer, with reference to UK and international guidance

An estimated 3.5 million people are currently living with cancer in the UK.[1] Thanks to advances in treatment, people are now living longer with a cancer diagnosis than ever before,[2] meaning that, for many people, cancer is a chronic illness that requires long-term management. However, those living with and beyond cancer often face ongoing late and long-term challenges related to their disease and/or its treatment, such as fatigue, cardiovascular disease, osteoporosis, neuropathic pain, cognitive impairment, and psychological distress.[3] Furthermore, the average lifespan is increasing, and the incidence of cancer rises with age.[4] Over one-third of new cancer diagnoses are in those aged 75 years or older,[5] many of whom are also living with other long-term health conditions.[6]

Patients with cancer were historically advised to rest, but current evidence suggests that exercise should be advocated to nearly everybody with a cancer diagnosis.[7] Despite clear benefits, however, exercise remains underutilised as a therapeutic intervention. According to a survey of 242 cancer survivors in the UK, 43% of respondents reported becoming less active following their cancer diagnosis.[8] Another survey of 3300 cancer survivors in England found that 31% of respondents had undertaken no physical activity in the preceding week.[9]

Patients with cancer may be unaware of the safety and value of physical activity, and healthcare professionals often lack the confidence, time, and resources to provide them with tailored advice.

Healthcare professionals working in general practice are ideally placed to bridge this gap. This article explores the role of general practice in supporting and empowering people living with and beyond cancer to increase their physical activity.

Guidelines on Exercise and Cancer

Several UK-specific and international guidelines make recommendations on exercise and cancer—including the following, many of which are discussed in this article:

- World Health Organization (WHO)—WHO guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour[10]

- World Cancer Research Fund—Exercise and cancer[11]

- American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM)—Exercise guidelines for cancer survivors[12]

- American Cancer Society (ACS)—Nutrition and physical activity guideline for cancer survivors[13]

- ACS—Guideline for diet and physical activity for cancer prevention[14]

- American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO)—Exercise, diet, and weight management during cancer treatment: ASCO guideline[15]

- Clinical Oncology Society of Australia (COSA)—COSA position statement on exercise in cancer care[16]

- Exercise & Sports Science Australia—The Exercise and Sports Science Australia position statement: exercise medicine in cancer management[17]

- UK Government—Physical activity guidelines: UK Chief Medical Officers’ report[18]

- NHS England—The cancer strategy section of the NHS long-term plan[19]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE)—Physical activity: brief advice for adults in primary care[20]

- NICE—Physical activity: exercise referral schemes.[21]

Evidence and Cancer: Evidence and Benefits

A substantial body of evidence demonstrates that exercise is beneficial for most people living with and beyond cancer,[22] and safe across many cancer types and stages.[12] Positive consequences of physical activity in people with cancer include:[7][22][23]

- improved physical function—cardiorespiratory fitness, muscle strength, and body composition

- reduced cancer-related fatigue and improved sleep

- reduced anxiety and depression, and improved body image and self-esteem

- improved health-related quality of life and physical and psychosocial outcomes

- increased readiness for cancer treatment (prehabilitation) and possibly improved treatment efficacy

- mitigation of comorbidities and treatment-related side effects and possibly improved adherence to treatment.

Cancer Recurrence and Survival

Data are limited on the effects of physical activity on cancer recurrence and survival; however, the ACS’s Nutrition and physical activity guideline for cancer survivors describes preliminary data on breast cancer suggesting that physical activity may reduce the risk of recurrence by 48%.[13][22][24]

Regarding survival, observational studies suggest that regular exercise may reduce cancer-specific mortality in breast, prostate, and colorectal cancers.[22][25] A prospective cohort study of 1535 cancer survivors aged 40 years or older in the US reported an approximately 30% reduction in the risk of cancer-specific mortality associated with exercise.[22][26]

The CHALLENGE Trial

Published in 2025, the CHALLENGE Trial is the first large-scale randomised controlled trial to demonstrate that structured exercise after treatment for colon cancer can significantly reduce the risk of recurrence and improve disease-free survival, with a magnitude of effect similar to that of many systemic anticancer treatments.[27] In this study, 889 people who had completed chemotherapy after surgery for bowel cancer were given either a 3-year, personalised exercise programme with the support of a personal trainer or general health education materials promoting exercise and nutrition.[27] The structured exercise programme led to a 28% lower risk of cancer recurrence, new primary cancer, or death compared with usual care.[27] After 8 years, the relative risk of death from any cause was 37% lower in the group given the exercise programme.[27] These results are astounding and confirm the role of physical activity as a therapeutic part of the cancer care pathway—moving beyond symptom management to directly influencing cancer outcomes.

An Opportunity for General Practice

General practice is the interface between hospital-based oncology services and community-based survivorship care. Patients usually transition back to general practice following active treatment, making healthcare professionals working in general practice the first point of contact for ongoing health needs.

Healthcare professionals working in general practice are ideally situated to raise the topic of exercise during follow up or chronic disease reviews, framing physical activity as a therapeutic intervention rather than an optional lifestyle choice and reinforcing similar messaging from cancer specialists. By embedding exercise into routine consultations, general practice has the opportunity to normalise physical activity as part of cancer recovery and treatment.

Starting the Conversation

It can be difficult to start a conversation about exercise. In one study examining patients’ views on integrating exercise into breast cancer care, healthcare professionals were hesitant to raise the topic despite patients’ wishes to receive support to be physically active.[28] The Moving Medicine website has some excellent resources to guide conversations around physical activity, with suggestions for 1-minute, 5-minute, or longer consultations.[29][30]

The 1-minute Conversation

The 1-minute conversation comprises three steps, designed to sow the seeds of change in someone’s mind in a way that makes it clear that you recognise what is important to them. There is no single way to do this, but these three questions may help achieve this objective in an effective and time-efficient way. Try these words in your own consultations and see how they work for you.

- ‘Would it be OK to spend a minute to talk about something that many patients with your condition find helpful?’

- ‘Many people with your condition find that moving more helps them to manage their condition and symptoms, as well as improving their general wellbeing. I wonder what you make of that?’

- ‘Would you be interested in talking a little more about how physical activity may help with your health and wellbeing on another visit?’

Adapted from: © Faculty of Sport and Exercise Medicine UK. The 1 minute conversation. movingmedicine.ac.uk/consultation-guides/the-1-minute-conversation

Reproduced with permission.

For some patients, the word ‘exercise’ can have negative connotations, perhaps because the experience of undergoing cancer treatment can lead to fatigue and physical limitations.[31] In addition, some people with cancer may not have exercised regularly prior to their diagnosis. Words like ‘movement’ or ‘being active’ may feel less threatening to some patients. Recognising patients’ unique circumstances, baseline and historical activity levels, personality types, and preferences, as well as treatment backgrounds and health profiles, may help healthcare professionals to tailor their exercise guidance to the individual.

Exercise in Cancer: What Does the Guidance say?

Physical activity during and after treatment for cancer is endorsed by the WHO[10] and the ACSM.[32] Most health bodies, including NICE and the UK Health Security Agency, recommend that all adults, including those with cancer, should aim for 150 minutes of moderate-intensity activity or 75 minutes of vigorous-intensity exercise each week, alongside strength training and activities that improve balance.[18][20][33] However, these targets are aspirational, and ‘any activity is better than none’.[33] Adults should also try to reduce the amount of time that they are sedentary—for example, when watching TV or sitting in front of a computer for long hours without a break.[33]

For examples of activities and their intensity, see Table 1,[33] and for general principles when starting an exercise routine that may be helpful to patients with cancer, see Box 2.[10][18][34]

Examples of Activity:

| Type of Exercise | Examples | Effects |

|---|---|---|

| Moderate intensity |

|

Being able to talk but not sing |

| High intensity |

|

Having difficulty talking without pausing |

| Strengthening and balance activities |

|

– |

| © Public Health England. Health matters: physical activity—prevention and management of long-term conditions. www.gov.uk/government/publications/health-matters-physical-activity/health-matters-physical-activity-prevention-and-management-of-long-term-conditions

Contains public sector information licensed under the Open Government Licence v3.0. |

||

General Principles When Starting an Exercise Routine

Start Slow and Build Gradually

Begin with short, gentle activities, such as a few minutes of walking, and gradually increase the duration and intensity over time.

Listen to Your Body

Pay attention to how you feel. Don’t push yourself too hard, especially if you’re feeling tired or unwell. Take rest days when needed. Remember that being short of breath while exercising is normal.

Be Consistent

Aim to build up to regular activity, even if it’s in short bursts. Doing something is better than doing nothing.

Safety Considerations

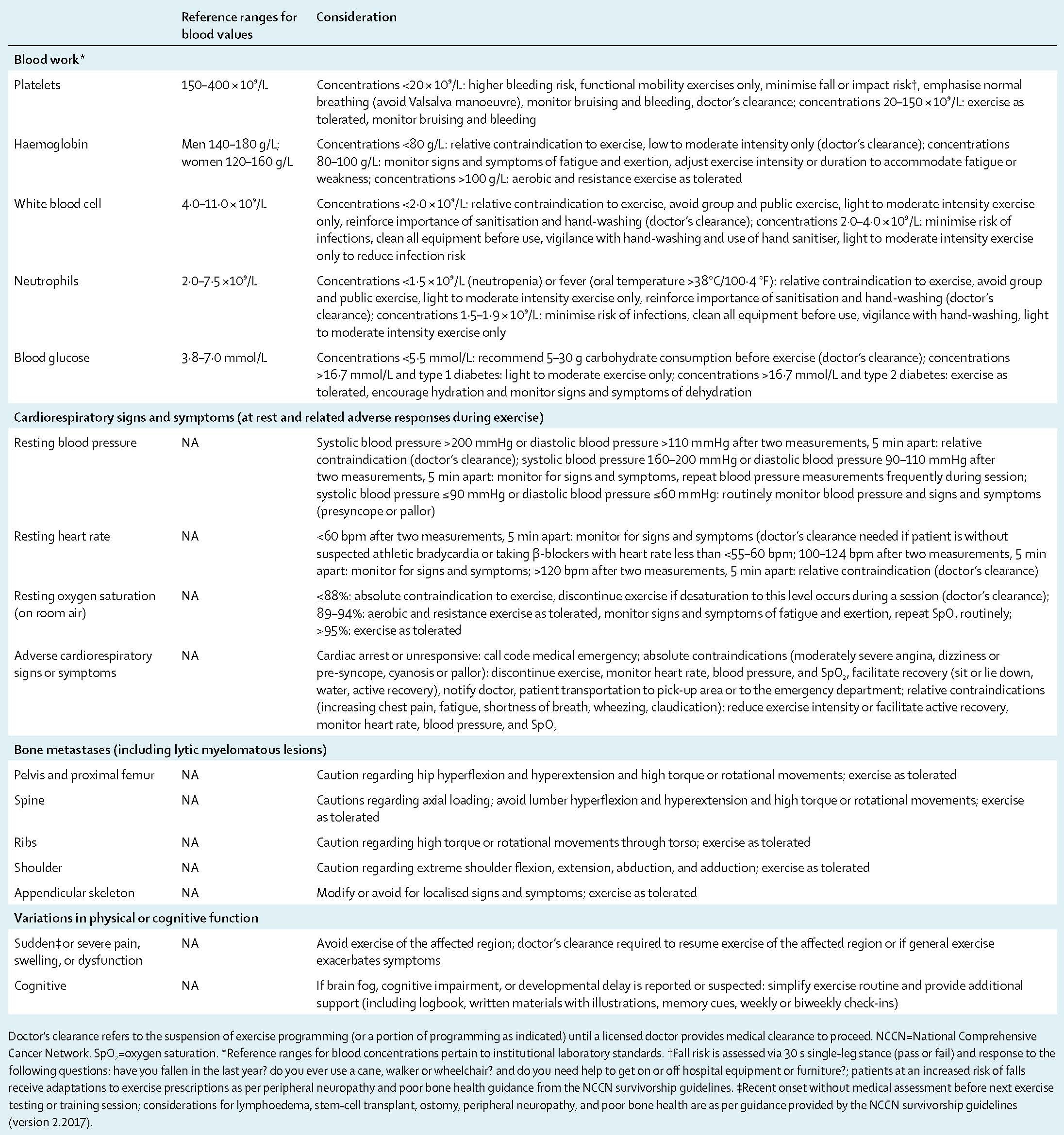

For nearly everyone with a cancer diagnosis, it is safer to be active than inactive.[35] However, although international guidelines on exercise and cancer state that physical activity is beneficial during and after cancer treatment, they do not discuss contraindications to exercise owing to a lack of evidence.[36] A more detailed safety reference guide to support exercise services for people with cancer is shown in Table 2.[36]

Safety Reference Guide to Support Exercise Services in People With Cancer:

Reprinted from Lancet Oncol, 19 (9), Santa Mina D, Langelier D, Adams S et al., Exercise as part of routine cancer care, E433–E436, © 2018, with permission from Elsevier.

Exercise and Bone Metastases

Macmillan Cancer Support has published some excellent guidance for healthcare professionals to support physical activity in people with metastatic bone disease (MBD).[37] Bone metastases are not a contraindication to exercise; although it is important to minimise the risk of fracture, physical activity within the capabilities of the person should be promoted and, when possible, people with MBD should aim towards guideline-recommended levels of physical activity.[37] However, exercise should be tailored to avoid metastatic sites at risk of pathologic fracture.[37] An individual’s physical activity regimen may also need modification over time, as the exercise capability of patients with MBD may change depending on treatment and disease progression.[37]

Bone pain that is new in onset or that has changed in nature or intensity in patients with MBD should be considered an indicator of fracture risk until proven otherwise.[37] In such patients, clinicians should order imaging studies, radiological review, and an orthopaedic opinion.[37]

Exercise and Lymphoedema

Historically, lymphoedema—the accumulation of lymphatic fluid leading to regional swelling—has been a concern in relation to exercise and, for many years, people with lymphoedema were advised to avoid strenuous upper- or lower-limb activity for fear of exacerbating symptoms.[38] However, evidence now suggests that appropriately prescribed exercise does not cause or worsen lymphoedema, and may in fact improve symptoms and function.[38]

Resistance training has been shown to be safe and beneficial, helping to maintain muscle mass, enhance limb strength, and reduce swelling.[38][39] Aerobic activities such as walking, swimming, and cycling are also recommended.[39] Patients may find this Move Against Cancer webinar about lymphoedema helpful.[40]

Referral

n an ideal world, all patients would be referred to tailored support services for individualised exercise guidance. Exercise specialists with a level-4 cancer rehabilitation qualification are ideally placed to provide this support, but it is not typically funded within the NHS.

Many areas have local cancer rehabilitation classes or other exercise support groups, such as 5K Your Way, Move Against Cancer; these can be found through the Cancer Care Map[41] and Macmillan websites.[42] Furthermore, charities such as Move Against Cancer[43] and Trekstock[44] offer one-to-one or group exercise sessions for younger people living with and beyond cancer.

For a case study demonstrating the benefits of community exercise classes and the 5K Your Way scheme for a patient with bowel cancer, see Box 3 (source: author’s experience).

Case Study

Julie, aged 70 years, presented to A&E with symptoms of bowel obstruction, and was diagnosed with stage-4 bowel cancer with liver metastases. On discharge from hospital, she needed a frame to mobilise, and was advised that she was not well enough for further treatment. Her GP and physiotherapist supported her to gradually build up her activity levels, and referred her to a community group exercise class for people with cancer.

Julie’s fitness improved such that, within 2 months, she was well enough to be offered chemotherapy that shrank her liver metastases. Despite chemotherapy, Julie continued to get fitter, joining her local 5K Your Way scheme and Move Against Cancer groups and, ultimately, getting fit enough to run 5 km with her friends and family.

Julie continued palliative chemotherapy for the next 2 years, maintaining her fitness with jogging, brisk walking, and strength training alongside practical and psychological support through the community exercise classes and the 5K Your Way group. Julie described exercise as: ‘the crutch that let me have treatment, but that also lets me focus on what I can do. When people ask me how I am, I don’t talk about the bad stuff, I tell them I’ve started running.’

A&E=Accident and Emergency; GP=general practitioner

Summary

Exercise is a safe, effective, and evidence-based intervention for people living with and beyond cancer. It improves physical function, alleviates common symptoms such as fatigue, anxiety, and depression, and plays a role in reducing recurrence and improving survival. With the CHALLENGE Trial[27] confirming its disease-modifying potential, there is now a clear imperative to embed physical activity into routine cancer care.

Healthcare professionals working in general practice are uniquely placed to start conversations, normalise movement as part of treatment and survivorship, and signpost patients to appropriate support, helping to ensure that exercise is recognised not as an optional lifestyle choice, but as an integral component of cancer management. The NHS needs to invest in exercise specialists and community exercise programmes to support patients with tailored and individualised exercise support.

Useful Resources

seful resources for healthcare professionals working in general practice and patients are shown below.

- NHS England—All our health: physical activity

- Moving Medicine—Welcome to PACC and Find the right consultation

- Sport England—Moving healthcare professionals

- PREP Development Team—PREP: preoperative risk education package

- South East London Cancer Alliance—Top tips on physical activity & cancer.

For Patients

- Centre for Perioperative Care—Fitter better sooner toolkit

- Cancer Research UK—Preparing for treatment and life afterwards (prehabilitation)

- NHS Greater Manchester—Prehab4cancer

- Macmillan Cancer Support—Exercising safely when you have cancer

- Move Against Cancer—Inspiring you to move against cancer and Lymphoedema—myths, evidence and taking control

- Trekstock—Get active

- Sport England—We are undefeatable.

PACC=physical activity clinical champions; PREP=preoperative risk education package

Implementation Actions for ICSs

written by Dr David Jenner, GP, Cullompton, Devon

The following implementation actions are designed to support ICSs with the challenges involved in implementing new guidance at a system level. Our aim is to help you to consider how to deliver improvements to healthcare within the available resources.

- Acknowledge that there is high-quality evidence of the benefits of regular exercise for both preventing and improving survival of certain common cancer types

- Publicise this to patients receiving cancer diagnoses (for example, via leaflets or web links)

- Encourage healthcare professionals to raise this, when appropriate, in cancer care reviews after new cancer diagnoses (although these are no longer a QOF requirement)

- Develop a suite of digital tools that can be used to support these discussions, possibly in conjunction with cancer charities

- Empower specialist cancer nurses, who help patients navigate the realities of a cancer diagnosis, to start discussions with patients using these tools.

ICS=integrated care system; QOF=Quality and Outcomes Framework

Footnotes

- Macmillan Cancer Support website. Cancer statistics in the UK. www.macmillan.org.uk/about-us/what-we-do/research/cancer-statistics-fact-sheet (accessed 3 October 2025).

2. Cancer Research UK. Cancer in the UK—overview 2025. London: CRUK, 2025. Available at: www.cancerresearchuk.org/sites/default/files/cancer_in_the_uk_overview_2025.pdf

3. Macmillan Cancer Support. Summary of potential consequences of cancer and its treatment. London: Macmillan Cancer Support. Available at: www.macmillan.org.uk/dfsmedia/1a6f23537f7f4519bb0cf14c45b2a629/11068-10061/Consequences_Of_Treatment_Summary

4. Macmillan Cancer Support website. Cancer prevalence. www.macmillan.org.uk/about-us/what-we-do/research/cancer-prevalence (accessed 3 October 2025).

5. Cancer Research UK website. Cancer incidence by age. www.cancerresearchuk.org/health-professional/cancer-statistics/incidence/age#heading-Zero (accessed 3 October 2025).

6. Macmillan Cancer Support. The burden of cancer and other long-term health conditions. www.macmillan.org.uk/dfsmedia/1a6f23537f7f4519bb0cf14c45b2a629/14730-10061/cancer-and-other-long-term-conditions-2015 (accessed 3 October 2025).

7. Garcia D, Thomson C. Physical activity and cancer survivorship. Nutr Clin Pract 2014; 29 (6): 768–779.

8.Orange S, Gilbert S, Brown M, Saxton J. Recall, perceptions and determinants of receiving physical activity advice amongst cancer survivors: a mixed-methods survey. Support Care Cancer 2021; 29 (11): 6369–6378.

9.NHS England, Department of Health. Quality of life of cancer survivors in England—report on a pilot survey using patient reported outcome measures (PROMS). London: NHS England, DH, 2012. Available at: assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/267042/9284-TSO-2900701-PROMS-1.pdf

10. World Health Organization. WHO guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO, 2020. Available at: www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240015128

11. World Cancer Research Fund website. Exercise and cancer. www.wcrf.org/preventing-cancer/topics/exercise-and-cancer (accessed 3 October 2025).

12.Campbell K, Winters-Stone K, Wiskemann J et al. Exercise guidelines for cancer survivors: consensus statement from international multidisciplinary roundtable. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2019; 51 (11): 2375–2390.

13.Rock C, Thomson C, Sullivan K et al. American Cancer Society nutrition and physical activity guideline for cancer survivors. CA Cancer J Clin 2022; 72 (3): 230–262.

14.Rock C, Thomson C, Gansler T et al. American Cancer Society guideline for diet and physical activity for cancer prevention. CA Cancer J Clin 2020; 70 (4): 245–271

15. Ligibel J, Bohlke K, May A et al. Exercise, diet, and weight management during cancer treatment: ASCO guideline. J Clin Oncol 2022; 40 (22): 2491–2507.

16. Clinical Oncology Society of Australia. COSA position statement on exercise in cancer care. Sydney, NSW, Australia: COSA, 2018. Available at: www.cosa.org.au/media/332488/cosa-position-statement-v4-web-final.pdf

17. Hayes S, Newton R, Spence R, Galvão D. The Exercise and Sports Science Australia position statement: exercise medicine in cancer management. J Sci Med Sport 2019; 22 (11): 1175–1199.

18. Department of Health and Social Care. Physical activity guidelines: UK Chief Medical Officers’ report. London: DHSC, 2020. Available at: www.gov.uk/government/publications/physical-activity-guidelines-uk-chief-medical-officers-report

19. NHS England website. NHS long term plan ambitions for cancer. www.england.nhs.uk/cancer/strategy (accessed 3 October 2025).

20. NICE. Physical activity: brief advice for adults in primary care. Public Health Guideline 44. NICE, 2013. Available at: www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ph44/resources/physical-activity-brief-advice-for-adults-in-primary-care-pdf-1996357939909

21. NICE. Physical activity: exercise referral schemes. Public Health Guideline 54. NICE, 2014. Available at: www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ph54/resources/physical-activity-exercise-referral-schemes-pdf-1996418406085

22. Yang L, Courneya K, Friedenreich C. The Physical Activity and Cancer Control (PACC) framework: update on the evidence, guidelines, and future research priorities. Br J Cancer 2024; 131 (6): 957–969.

23. Cancer Research UK website. Preparing for treatment and life afterwards (prehabilitation). www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/treatment/prehabilitation (accessed 3 October 2025).

24. Morishita S, Hamaue Y, Fukushima T et al. Effect of exercise on mortality and recurrence in patients with cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Integr Cancer Ther 2020; 19: 1534735420917462.

25. McTiernan A, Friedenreich C, Katzmarzyk P et al. Physical activity in cancer prevention and survival: a systematic review. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2019; 51 (6): 1252–1261.

26. Cao C, Friedenreich C, Yang L. Association of daily sitting time and leisure-time physical activity with survival among us cancer survivors. JAMA Oncol 2022; 8 (3): 395–403.

27. Courneya K, Vardy J, O’Callaghan C et al. Structured exercise after adjuvant chemotherapy for colon cancer. N Engl J Med 2025; 393 (1): 13–25.

28. Gokal K, Daley A, Madigan C. ‘Fear of raising the problem without a solution’: a qualitative study of patients’ and healthcare professionals’ views regarding the integration of routine support for physical activity within breast cancer care. Support Care Cancer 2024; 32 (1): 87.

29. Moving Medicine website. Find the right consultation. movingmedicine.ac.uk/consultation-guides/find-the-right-consultation (accessed 3 October 2025).

30. Moving Medicine website. The 1 minute conversation. movingmedicine.ac.uk/consultation-guides/the-1-minute-conversation (accessed 3 October 2025).

31. Andersen C, Adamsen L, Sadolin Damhus C et al. Qualitative exploration of the perceptions of exercise in patients with cancer initiated during chemotherapy: a meta-synthesis. BMJ Open 2023; 13 (12): e074266.

32. Campbell K, Winters-Stone K, Patel A et al. An executive summary of reports from an international multidisciplinary roundtable on exercise and cancer: evidence, guidelines, and implementation. Rehabil Oncol 2019; 37 (4):144–152.

33. Public Health England website. Health matters: physical activity—prevention and management of long-term conditions. www.gov.uk/government/publications/health-matters-physical-activity/health-matters-physical-activity-prevention-and-management-of-long-term-conditions (accessed 3 October 2025).

34. Mayo Clinic website. Fitness program: 5 steps to get started. www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/fitness/in-depth/fitness/art-20048269 (accessed 3 October 2025).

35. Macmillan Cancer Support website. Exercising safely when you have cancer. www.macmillan.org.uk/cancer-information-and-support/treatment/preparing-for-treatment/physical-activity-and-cancer/exercising-safely (accessed 3 October 2025).

36. Santa Mina D, Langelier D, Adams S et al. Exercise as part of routine cancer care. Lancet Oncol 2018; 19 (9): E433–E436.

37. Macmillan Cancer Support. Physical activity for people with metastatic bone disease. London: Macmillan Cancer Support. Available at: www.macmillan.org.uk/dfsmedia/1a6f23537f7f4519bb0cf14c45b2a629/1784-source/physical-activity-for-people-with-metastatic-bone-disease-guidance-tcm9-326004.pdf

38. Hasenoehrl T, Palma S, Ramazanova D et al. Resistance exercise and breast cancer-related lymphedema—a systematic review update and meta-analysis. Support Care Cancer 2020; 28 (8): 3593–3603.

39. Cancer Research UK website. Exercise, positioning, and lymphoedema. www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/coping/physically/lymphoedema-and-cancer/treating/exercise (accessed 3 October 2025).

40. Move Against Cancer YouTube channel. Lymphoedema—myths, evidence and taking control. Video webinar. Available at: www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ck4qIpEG0cw

41. Cancer Care Map website. Find cancer support services near you. www.cancercaremap.org/search-page (accessed 3 October 2025).

42. Macmillan Cancer Support website. Find local cancer support services. www.macmillan.org.uk/cancer-information-and-support/in-your-area (accessed 3 October 2025).

43. Move Against Cancer website. Inspiring you to move against cancer. www.moveagainstcancer.org (accessed 3 October 2025).

44. Trekstock website. Get active. www.trekstock.com/get-active (accessed 3 October 2025).